The Mechanisms Between Heat and Cold Stress

Employers and safety managers have long looked to flame-resistant (FR) and arc-rated (AR) garments to help protect workers from injury due to flash fire and arc flash. Because these garments are designed using specially engineered, self-extinguishing fabrics and are certified to rigorous testing standards, they can help prevent or lessen the severity of injury.

Utilizing FR/AR garments as part of a comprehensive PPE (personal protective equipment) program is one of the ways employers can meet their obligation to “provide workers with employment and a place of employment that are free from recognized hazards.”1

Questions arise, however, when outside temperatures rise - or plummet. Is it possible to maximize protection while at the same time minimizing the risk of heat stress and cold stress? The answer is yes, but finding the right solution requires an understanding of several interrelated factors, one of them being how our body responds to hot and cold weather situations.

Let’s start with heat. Our bodies are continuously working to maintain homeostasis in regard to our core temperature, which is approximately 98.6 degrees. However, when outside temperatures rise, our bodies can overheat, and the excess must be released to avoid heat-related illness.

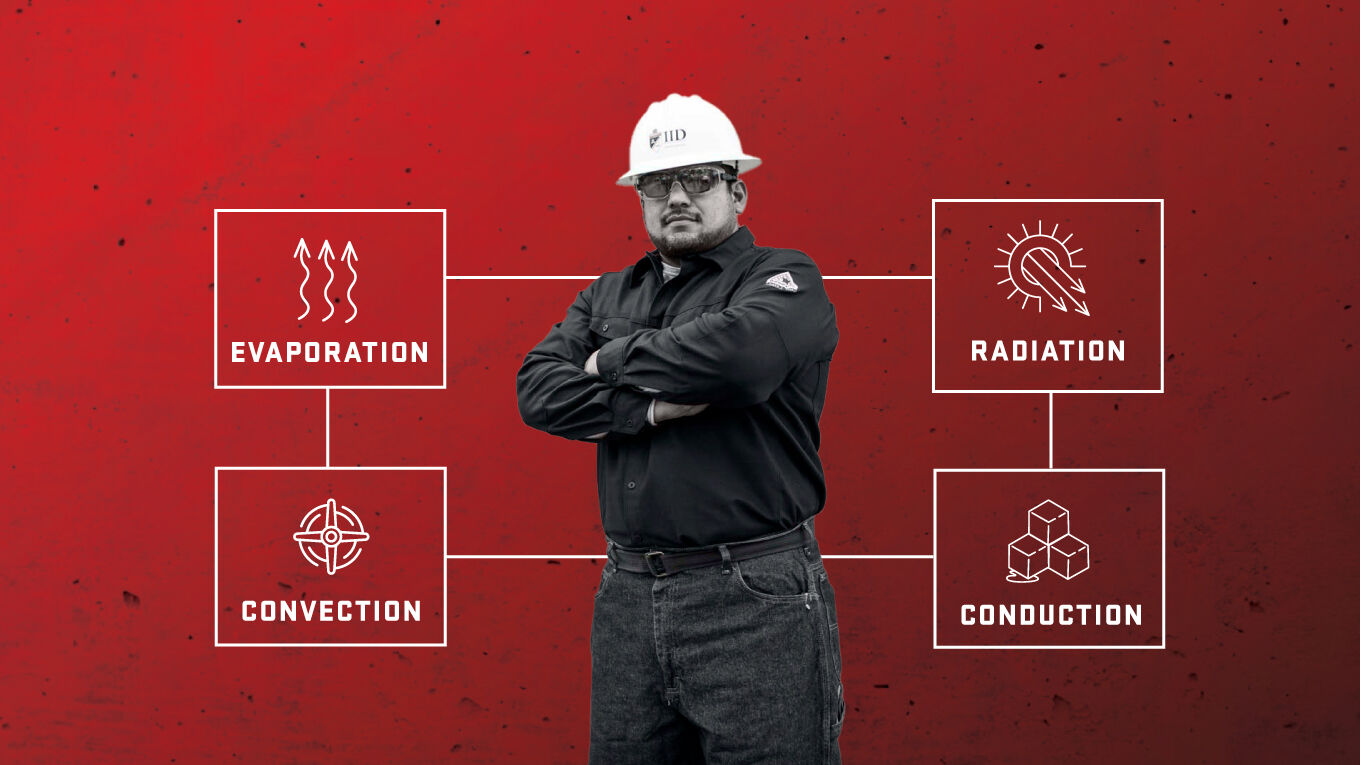

Heat flows from warmer environments - in this case our bodies - to cooler environments - the outside air. Our bodies’ natural cooling happens via four mechanisms:

• Radiation: Heat radiates through the skin and is absorbed by the surrounding, cooler air.

• Conduction: Direct contact with a cooler object, like cool water, cools the body.

• Convection: Air moving across the skin, such as from a breeze or fan, cools the body.

• Evaporation: Water from our blood absorbs heat, which rises to the skin’s surface as sweat and evaporates to cool the body.

Anytime the outside temperature rises, the combination of the radiant heat load and the worker’s exertion level can lead to heat stress. This is the name for multiple heat-related illnesses, including (from mild to severe) heat rash, heat cramps, heat exhaustion and heat stroke. The first three of these can be reversed with hydration, rest and shade when acted on early. Heat stroke requires prompt medical intervention and can cause permanent disability or even death.

Clothing of any type keeps the body’s natural heat-releasing mechanisms from working efficiently. In addition, once the outside temperature exceeds the body’s internal temperature, these four mechanisms are reduced to just one - evaporation. The result can be excessive sweating and subsequent dehydration. Experiencing dehydration of just 3% can cause a 17% reduction in reaction time, which can lead to accidents.

Interestingly, sweat plays a leading role in cold weather safety, as well. When workers are bundled up and exerting energy, sweat can build up under their clothing. Once their activity level decreases, this moisture cools and the body’s temperature can drop. Cold stress refers to multiple cold-related conditions and illnesses, including chilblains, trench foot, frostbite and hypothermia. All are reversible with dry shelter, warmth and rest, except for hypothermia, which, like its heat-related counterpart, heat stroke, requires immediate medical attention.

Note that in both hot weather and cold, temperatures don’t have to be extreme for workers to feel the effects of stress. Most of us have experienced becoming chilled soon after working up a sweat… even on a summer day. Understanding your FR/AR clothing and its various features can help mitigate the effects of both heat and cold, no matter how extreme or mild the weather.

In addition to understanding how bodies respond to weather, building the right combination for your workers requires an understanding of:

• How various fibers and fabrics can help keep workers cool

• How layering can help keep workers warm

• Effective jobsite engineering controls

With these tools in hand, workers should be able to manage their body temperatures throughout the day and take action as needed to maintain their health and safety.

1 Occupational Safety and Health Act, Section 5(a)(1), 1970.